Corporate Handout Politicking Kills Small Businesses

PLUS: A big win from Treasury, and Odessa Kelly tries to turn Nashville incentive politics on their head.

This is Boondoggle, the newsletter about corporations ripping off our states and cities. If you’re not currently a subscriber, please click the green button below to sign up. Thanks!

One of the major problems with communities doling out tax breaks and other favors to large corporations is that doing so disadvantages their own, local, usually smaller, businesses. After all, those monetary favors lower costs for the big guys, making it easier for them to “compete” against smaller entities that don’t receive public largesse.

What corporate giveaways do accomplish, though, is building political capital for the politicians who dole them out, as they get to stand next to some big-name corporate executive and extol the virtues of their actions, pointing to the jobs they supposedly created and the economic activity they initiated, getting their face on local news and in the paper, while sending out glowing tweets and Facebook posts.

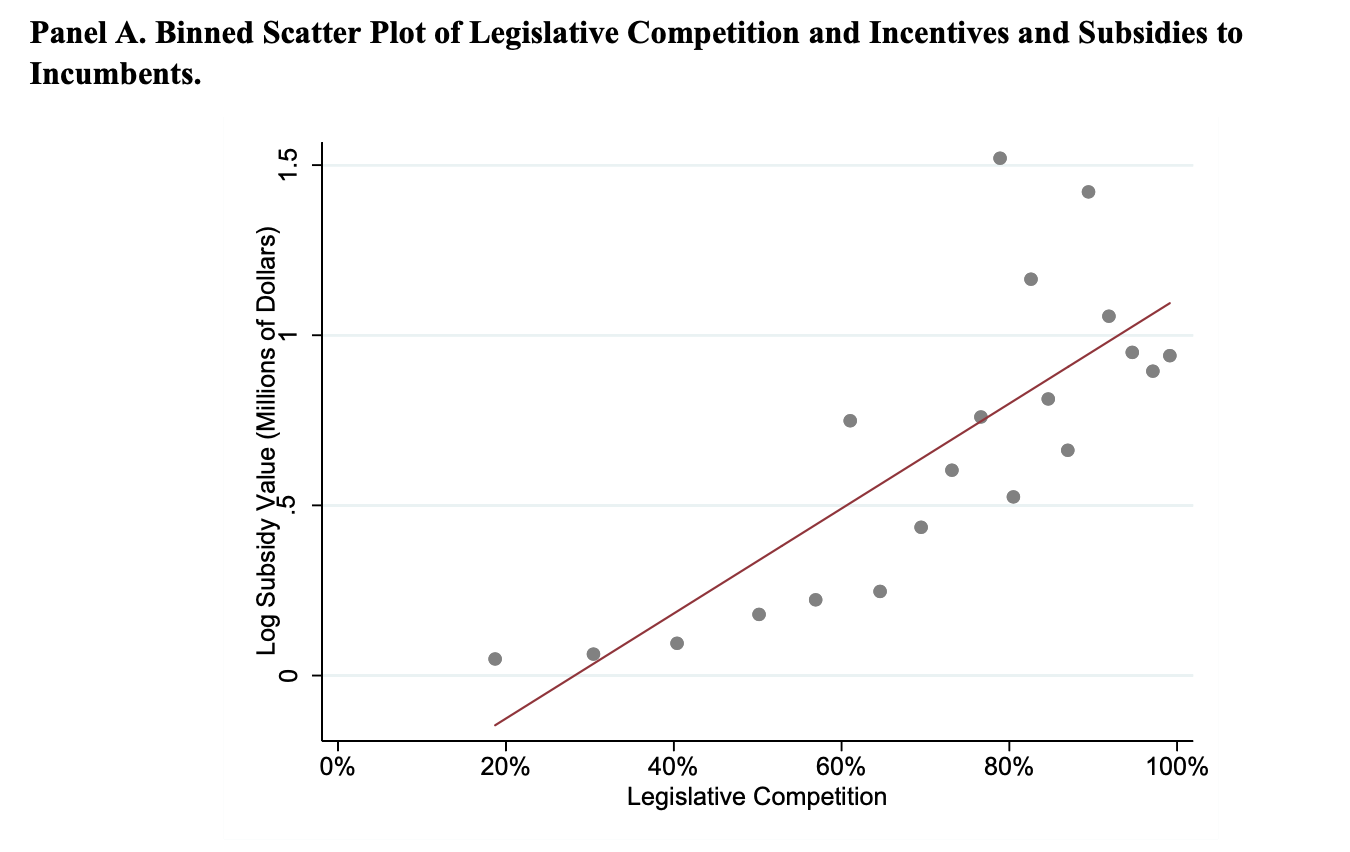

In a fascinating new paper, Manav Raj of the Stern School of Business at New York University ties all of these strands together. He found that states with more competitive legislatures hand out more corporate largesse, and then see more small businesses fail to succeed against larger, incumbent firms.

As Raj explained in the paper (and many thanks to him for sharing a copy with me), “When legislative competition is high, well-connected incumbent firms are better able to leverage familiarity, access, and influence to take advantage of this opportunity and transform the institutional environment. Policy rewards to well-connected incumbent firms may have negative consequences for younger, less-connected firms and implications for the entrepreneurial environment.”

Essentially, more politicking is better for big corporations seeking handouts and worse for new businesses trying to make inroads against dominant competitors. Here’s Raj’s chart on how this effect can be seen broadly across legislatures.

Prior academic work has shown that corporate handouts help politicians with their re-election campaigns, which is why their use at the state level goes up in years in which a governor is up for re-election. So it makes sense that high levels of legislative competition — meaning tiny majorities for the party in power, and a higher likelihood that a legislative chamber can flip from one party to another — make handouts to incumbent, dominant firms more likely. In those instances, legislators on the margins need more political capital to win re-election and have more power to extract concessions during legislative debates because their votes are more valuable.

Why are their votes more valuable? Well, when a majority is tiny — like in the U.S. Senate at the moment — each member has the power to put their vote up for sale in a way that lawmakers who are part of a massive majority can’t, since in the latter situation the party in power can afford to lose votes and still enact its agenda. To continue with the U.S. Senate as an example, because Democrats need Sen. Joe Manchin’s vote on everything they want to pass, he becomes, only somewhat jokingly, President Manchin. And, of course, business interests know the situation in a particular legislature, and make the most of it.

Raj also found corporate handouts increase alongside increases in political donations by businesses, creating a toxic stew of back-scratching that entrenches those corporations that play politics best, even if they don’t provide the best service to customers or do very much in the way of innovating. It makes more sense for them to spend money on political campaigns and lobbying shops than R&D.

All of this is bad for small firms. They already have an array of obstacles placed before them without having to worry about their larger competitors getting the government to cover a percentage of their operational costs. And indeed, Raj found that states that hand out more incentives see more new business fail to launch.

As he wrote, “The findings indicate that increased legislative competition creates an institutional environment that favors entrenched incumbents over younger firms, and thereby increases young firm mortality.” New businesses just can’t keep up with the political power of entrenched incumbents.

Raj’s important findings add to the evidence showing that the corporate giveaway issue is a political problem, not an economic one. Elected officials are using incentives to juice their vote totals, not local economies.

Of course, you could read his study as a case for one-party rule: Less competition, fewer corporate handouts, more small business success. Viola! But that’s not really what I’m going for here.

What’s needed is to flip the current political incentive structure on its head, making it more politically valuable to disavow handouts than to take them — or finding ways for more responsible leaders to join together to eliminate incentives without any one person having to pay the political price. That’s the motivation behind the interstate compact against corporate giveaways, for instance.

As Raj’s study makes clear, doing so is not only about preventing the waste of taxpayer money, but ensuring that small, local firms have a chance to get off the ground and thrive.

SHAMELESS SELF-PROMOTION: I had a piece in Mic last week on the power wielded by tax prep corporations Intuit and H&R Block and why it makes paying taxes more painful than it has to be. You can read it here.

UPDATE: Last month I wrote about how the latest coronavirus relief bill passed by Congress included a provision that could help block new state and local corporate handout programs. On Monday, Treasury released its full version of that rule, and a Treasury spokesperson confirmed it does apply to state and local incentives.

Hive fives all around! If Treasury enforces this, it could be a really big deal for cutting back on the sort of stuff I write about in this newsletter every week.

ONE MORE THING: Nashville’s city council last week approved a deal to bring a new Oracle campus to town. The agreement stipulates that Oracle will spend $175 million on building some public infrastructure, including a pedestrian bridge and a park, and will receive 50 percent of its property tax payments back until that $175 million is repaid.

As these things go, it’s not the worst, though it is a little weird to outsource public infrastructure to a private corporation. There are also very legitimate concerns about residents being displaced around the new campus. The city says it will spend revenue raised by the deal on affordable housing, but we’ve heard that one before.

The reason I’m bringing all this up, though, is that a local activist who is running for Congress named Odessa Kelly talks about these deals the way I wish more political folks would. This is from a press conference before the agreement was approved:

Oracle isn’t the prize, Nashville is the prize. If we set expectations, the companies that are coming here are going to meet those expectations because they want to be in Nashville. Don’t make this the other way around, as if we’re going to lose something if Oracle or all these other companies go somewhere else. There’s a reason they chose Nashville.

“Oracle isn’t the prize, Nashville is the prize.” Right on. You can watch more here.

Thanks for reading this edition of Boondoggle. If you liked it, please take a moment to click the little heart under the headline or below. And forward it around to friends, family, or neighbors using the green buttons. Every click and share really helps.

If you don’t subscribe already and you’d like to sign up, just click below.

Finally, if you’d like to pick up a copy of my book, The Billionaire Boondoggle: How Our Politicians Let Corporations and Bigwigs Steal Our Money and Jobs, go here.

Thanks again!

— Pat Garofalo