Corporate Tax Breaks, Mob-Style

A New Jersey indictment highlights the nexus between economic development and corruption.

This is Boondoggle, the newsletter about how corporations rip off our states, cities, and communities, and what we can do about it. If you’re not currently a subscriber, please click the green button below to sign up. Thanks!

It’s a tad cliche (and for those of us who grew up in the Garden State, often a tad insulting) to liken things that happen in New Jersey to organized crime. The Sopranos comparisons are often too easy and lazy.

But sometimes, the cement shoes fit.

This week, New Jersey Attorney General Matthew Platkin indicted South Jersey political power broker George Norcross and several of his family members and associates, including former elected officials, on 13 counts of violating racketeering law. According to the indictment, the “Norcross Enterprise” allegedly created a criminal conspiracy that used threats, coercion, and intimidation to control a wide swathe of the waterfront in Camden, New Jersey, one of America’s poorest cities.

And at the heart of the case is a corporate subsidy program, highlighting the nexus between corporate tax handouts and corruption that is very often there but not usually this blatant.

Per the indictment, which was unsealed on Tuesday, George Norcross’ brother, Philip Norcross, a state lobbyist, and Donald Norcross, then a state legislator and now a Congressman, helped author and usher through the statehouse a corporate subsidy program called Grow New Jersey, which was part of an economic development package approved in 2013. The program was tailor-made to allow George Norcross’ Camden-based businesses to take advantage of a slew of subsidies.

George Norcross then intimidated and threatened other developers and non-profits in Camden to turn over valuable land and property rights, so as to access those public dollars and consolidate control of the most lucrative part of the city.

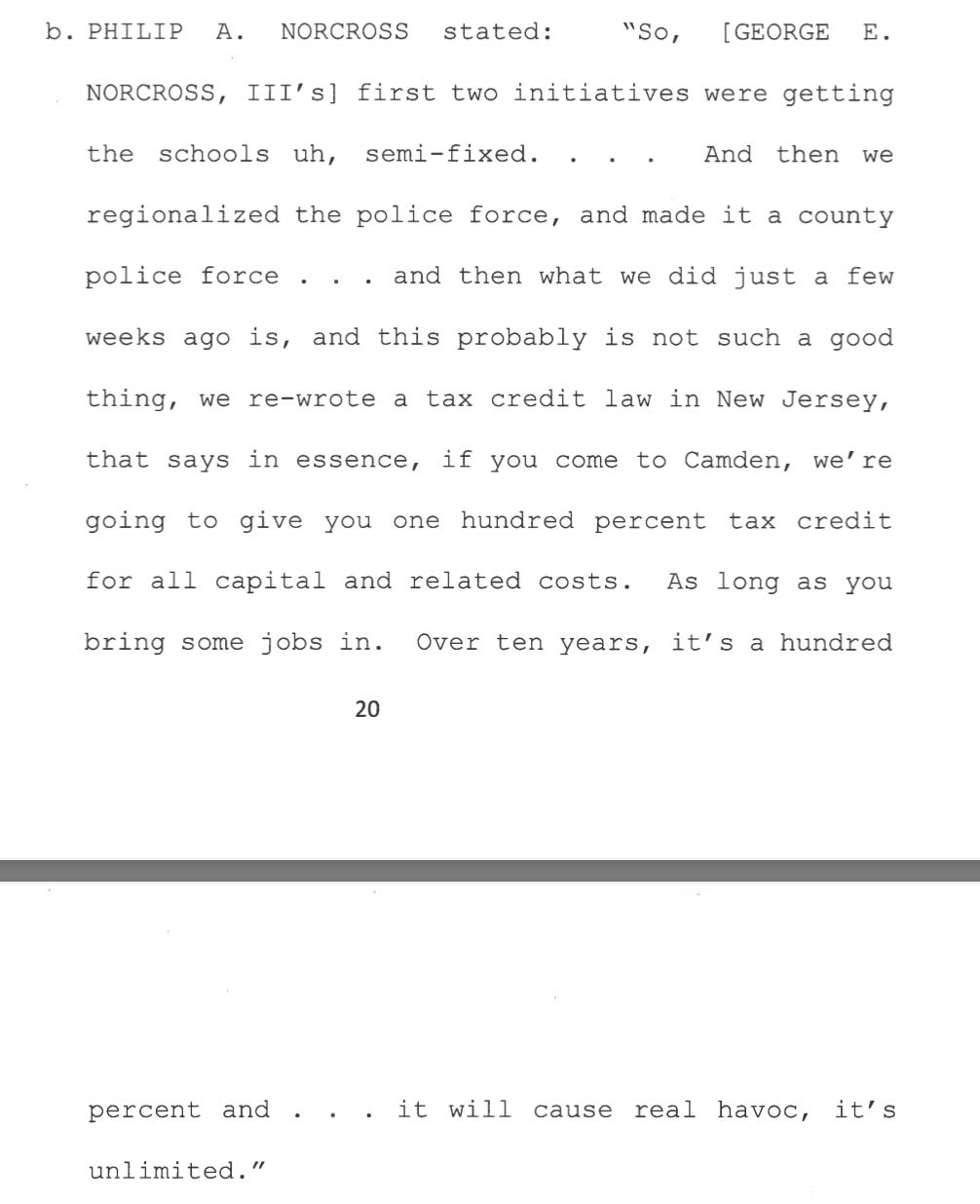

I’ve written before about some aspects of New Jersey’s economic development system that seemed pretty darn corrupt, but the indictment lays out many more of the sordid details. For example, Phillip Norcross knew the program he helped create was actually bad for the public and would wreak “havoc,” as this bit of a recorded conversation reveals:

George Norcross — who controlled the South Jersey Democratic political machine despite never holding public office himself — then used a slew of threats and intimidation to push developers away from the Camden waterfront, so only he and his associates would access the available public funds. For example:

The criminal enterprise Norcross allegedly created filtered tens of millions of public dollars — at least — into businesses he either owned or was associated with, per the indictment. And, as I’ve noted before, Camden itself hardly benefitted at all from this public spending, with actual Camden residents filling very few of the jobs the money supposedly created.

“On full display in this indictment is how a group of unelected, private businessmen used their power and influence to get government to aid their criminal enterprise and further its interests,” Platkin said. “The alleged conduct of the Norcross Enterprise has caused great harm to individuals, businesses, non-profits, the people of the State of New Jersey, and especially the City of Camden and its residents. That stops today. We must never accept politics and government — that is funded with tax dollars — to be weaponized against the people it serves.”

This is a seismic event in New Jersey politics. It’s hard to overstate the power and influence Norcross and his associates held in the state. It’s a huge deal that a Democratic attorney general is attempting to take him off the board, once and for all. And Norcross himself is certainly not going quietly; he literally sat in the front row of the press conference where Platkin announced the charges.

Beyond the state-specific political ramifications, the case also highlights a persistent problem in corporate subsidy programs that extends well beyond New Jersey: They’re too easily corruptible, and they create a vicious feedback loop between political actors and politically connected corporations. In fact, the indictment had its genesis in an investigation into ineffective corporate subsidy programs that New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy initiated years ago (even if that investigation resulted in very little in the way of policy changes).

Long-time readers might recognize much of this next section, but I wanted to cover it again for newer readers. And a refresher is always good, right?

There’s a very clear connection in academic literature between corporate subsidies, political donations, and ultimately corruption. For example, one study found that more corporate subsidy spending in a state results in higher campaign contributions for incumbent politicians. Specifically, when a state starts dishing out “large” subsidies, defined as a big jump from the historical baseline, “Annual campaign contributions increase by approximately 38.4% (or $738,100) in the average state from construction and labor unions, 20.5% (or $158,600) from lobbyists and lawyers who represent large firms in the political process, and 106.8% (or $122,000) from large business advocacy and trade organizations.”

Another study found that if a corporation makes state-level campaign contributions, it “is nearly four times more likely to receive an [incentive] award, and the award is 63 percent larger.” Finally, a 2016 study found “that a greater number of lobbyists and campaign contributions from businesses leads to more subsidy spending, all else equal.”

That’s just donations, not the sort of illegal corruption alleged in the New Jersey case, but its still problematic for policy and for the ability of local businesses to fairly compete in the market when their dominant competitors are being propped up with public dollars thanks to politicians who are raking in campaign cash from those very corporations.

But there’s more that’s more directly connected to actual illegality. According to a study by the Kansas City Federal Reserve, locales with more “troubled political cultures” spend more money on corporate subsidies. Specifically, “increasing the rate at which government officials are convicted of federal corruption crimes by 1 per 100,000 residents over a 13 year period is associated with a 2.9 percent greater chance that a community will offer business incentives.” Willingness to cross the line into criminality correlates with, again, a too-cozy relationship between certain select corporations and elected lawmakers doling out cash to each other.

With that sort of history, then, it makes sense that New Jersey — a place that indeed has a troubled political culture if the term has any meaning — would wind up here. Maybe, in addition to trying to take down the mob boss, go fix the subsidy programs at the heart of the case too?

Thanks for reading this edition of Boondoggle. If you liked it, please take a moment to click the little heart under the headline or below. And forward it to friends, family, or neighbors using the green buttons. Every click and share really helps.

If you don’t subscribe already and you’d like to sign up, just click below.

Thanks again!

— Pat Garofalo