This is Boondoggle, the newsletter about how corporations rip off our states, cities, and communities, and what we can do about it. If you’re not currently a subscriber, please click the green button below to sign up. Thanks!

Despite the rate of inflation having eased in recent months, costs are still considerably higher than they were just a few years ago. That reality has turned into a potent political issue, as shown by the recent election results in which high cost of living clearly motivated voters to hit the polls.

One area of consistent complaint is utility costs. One in five people reported having been late on at least one utility bill in 2023, and even in parts of the country where other costs are easing, utility costs continue to climb. Electric and gas utilities last year requested a record-setting amount of rate increases, at $18.13 billion, marking the third consecutive year in which a new record was set. In some areas, utility rates have tripled over the last decade.

But this isn’t some inexorable fact of the market or the current economy, some immutable line item on a household budget over which policymakers have no power. For reasons I’ll explain below, utility costs are rigged against consumers in many ways, but good regulators can still stand up for ratepayers and protect them from relentless rate increases — and should do so on both policy and political grounds.

In fact, in Connecticut recently, the Public Utilities Regulatory Authority (PURA) — chaired by perhaps the best utility regulator in the country, Marissa Gillett — did just that. PURA not only rejected a rate increase requested by two of the state’s natural gas utilities, but actually lowered the profits those two utilities will be able to make next year, thereby lowering monthly bills for Connecticut residents.

These things can happen, with enough political will.

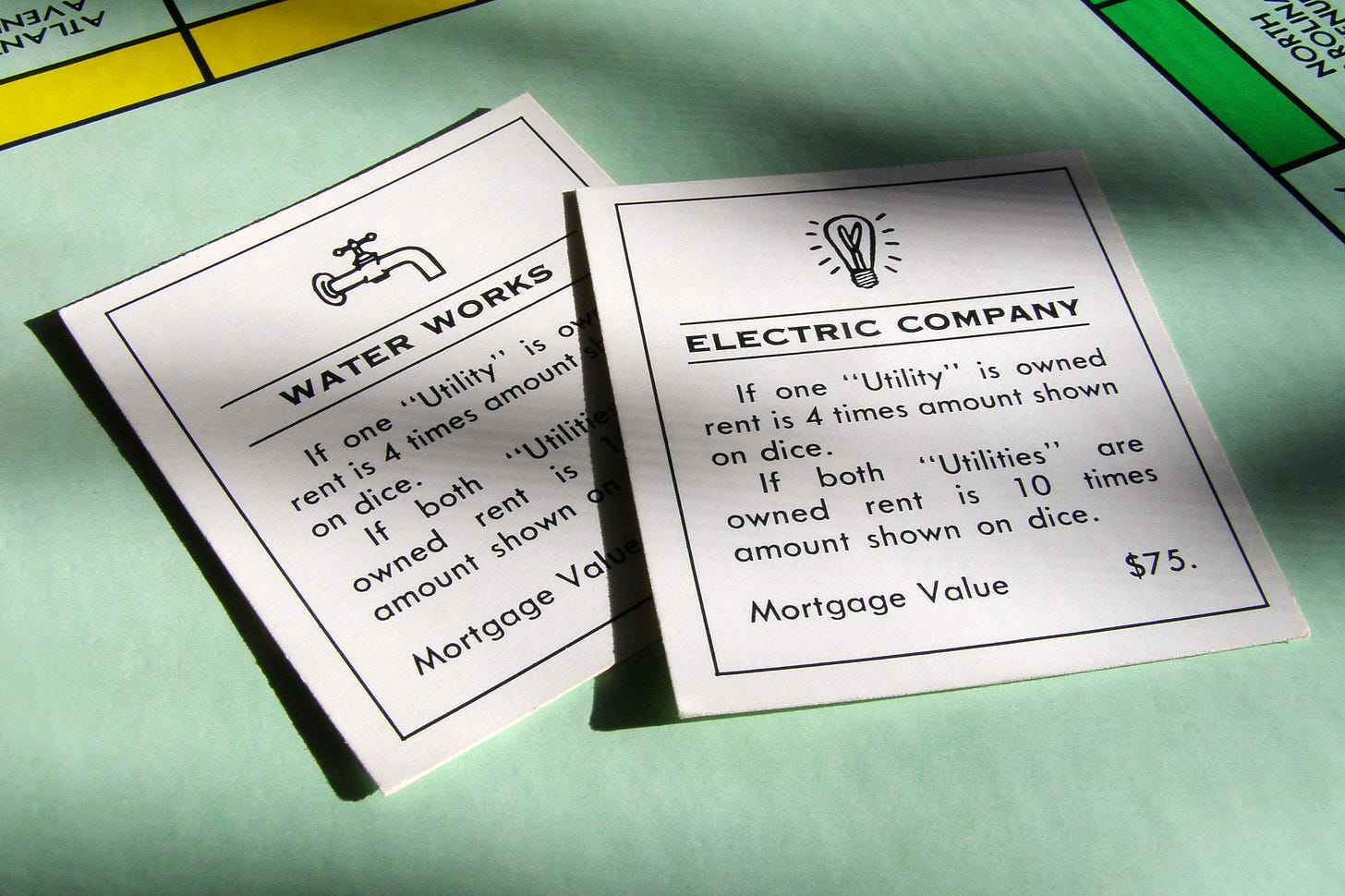

Utilities occupy an odd place in the American economy. Mostly regulated at the state level, they are the classic example of a natural monopoly, granted exclusive or semi-exclusive rights over certain territories due to the reality that building two or more sets of the same infrastructure for power or water or whatever is impractical.

But many monopoly utilities are also investor-owned, meaning they owe returns to private owners, even as they perform very public duties. Those rates of return are determined by public bodies — generally known as public utilities commissions — that are either elected (11 states) or appointed by other elected officials (the other 39, plus D.C.). While investor-owned utilities constitute only 6 percent of the total number of utilities in the U.S., they serve more than 70 percent of electricity customers and nearly all natural gas customers.

Part of the reason monopoly utility rates are going up so dramatically for so many folks is the way which those rates are determined. As some of my colleagues wrote in a recent report, the formulas and incentives built into the process are a mess, encouraging utilities to overspend on wasteful stuff and then recoup those costs, plus a percentage, by charging ratepayers more. “Essentially this means utilities earn profit when they spend money, at the expense of customers, and lose money when they save money to the benefit of customers and national strategic interests,” they wrote.

Utilities are also allowed to earn rates of return above their cost of capital, meaning they can return more to investors than they need to in order to attract that investment (i.e., investors would still invest at lower rates). This is simply a wasted transfer from consumer to investors totaling billions of dollars per year.

A 2019 study of U.S. utilities found that regulators have, for years, been increasing the amount of return they allow utilities to make when compared to other safe, stable investments, “highlighting a disconnect between what regulators claim to be doing and what they are actually doing.” In other countries, including the UK, Australia, and Canada, rates of return are closer to the cost of capital for monopoly utilities, with no noticeable drop in outcomes for customers.

Baked on top of these structural issues is some good old-fashioned corruption. Regulators are also often captured by the industry, either due to revolving door-style appointments in which regulators come from or immediately go to work for the very industries they regulate, or due to the political donations regulators need to solicit in order to win seats, or to the donations solicited by the leaders who appoint them. This results in consumers and other interest groups — such as, say, clean energy advocates or environmentalists — receiving far less representation on regulatory bodies than the utility industry itself.

Monopoly utilities are also allowed to engage in extensive politicking, including running ads, lobbying via trade associations, and lobbying state legislatures, for which they can charge ratepayers.

Stir that all together and you have a situation in which, when monopoly utilities ask for a rate increase, they usually receive it, or at the very least are not told by regulators that they actually need to do more with less in order to save ratepayers money.

But not always, as shown by Connecticut. There, Connecticut Natural Gas had sought a $19.7 million increase in revenue for next year, but received a decrease of $24 million, while Southern Connecticut Gas had sought a $43 million increase, but received an $11 million decrease. According to the Connecticut attorney general’s office, Connecticut Natural Gas customers will save approximately $7 to $8 per month due to this decision, while Southern Connecticut Gas customers will save about $3.50 to $4 per month.

“Their rate demands were packed with inflated profits and unnecessary expenses. PURA was absolutely right to slash their revenue,” said Connecticut Attorney General William Tong.

Indeed, all it took was a regulator saying no, bucking the conventional wisdom, and ignoring the onslaught of bad faith criticism from the utilities and their allies, and Connecticut ratepayers saw their costs go down, with all the legal boxes having been checked. Yes, those costs are only decreasing by a few dollars a month, but they are decreasing, when every other cost seems to be going up.

This is certainly not the only instance of a regulator decreasing revenue for a major utility in recent years, but it’s rare enough that it stood out, at least to me — and, again, at a moment in which prices are even more politically salient than normal.

“By law, [the utilities] are required to demonstrate, they have the burden of proving that what they're asking for is a just and reasonable rate, et cetera. And for decades — I mean, I wouldn't hazard to guess how long — they have succeeded in getting that request, either through settlements or something else. And they have gotten used to not having to meet that burden,” Gillett has said.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont earlier this year backed Gillett, reappointing her for a second term as PURA chair, a good way to bake in the positive changes Connecticut households are seeing. State legislators could also make statutory changes that would tie the hands of the regulators in ways that would benefit consumers.

At the end of the day, utilities is a sanitized word for the things — water, heat, lights — we all need to actually survive in the world. I think there’s political capital to be built for anyone in a leadership position who can do something about the ever-climbing costs households are facing — and one way to get there is to appoint more regulators like Gillett, who will actually stand up to entrenched power that is used to simply getting its way.

SIMPLY STATED: Here are links to a few stories that caught my eye this week.

Virginia launched a task force aimed at reducing the negative effects of social media on the mental health of children.

The Michigan legislature extended a tax break for data centers “that brought only 2.6% of promised jobs.”

There are more junk fees cropping up in the rental housing industry.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom said his state could begin offering rebates for electric vehicle purchases if the Trump Administration eliminates the federal version.

Thanks for reading this edition of Boondoggle. If you liked it, please take a moment to click the little heart under the headline or below. And forward it to friends, family, or neighbors using the green buttons. Every click and share really helps.

If you don’t subscribe already and you’d like to sign up, just click below.

Thanks again!

— Pat Garofalo

How did Connecticut argue for the cut? Why gas and not electric?

The inflation of last few years and rise in rates is hurting that ROE so I expect utilities will ask for increases still.