Inside the Fight to Save Local Journalism

State and federal lawmakers are aiming at Big Tech's ability to destroy local news.

This is Boondoggle, the newsletter about corporations ripping off our states, cities, and communities. If you’re not currently a subscriber, please click the green button below to sign up. Thanks!

It’s no secret that local journalism is in crisis. 32,000 newsroom employees have been laid off in the last decade alone, and 60 percent of U.S. counties have no daily news coverage. And the coverage that remains is, well, let’s just say, not great.

Vist the website of any small or regional newspaper and you’re likely to be bombarded by endless pop-up ads and autoplay videos. If you can manage to slog past them, it earns you the chance to read whatever local coverage the skeleton staff can scrape together, plus syndicated national content you can find literally anywhere else. The few papers that have any semblance of a reporting team left inevitably get acquired by private equity firms and picked over for scraps.

Local reporters cover absurdly large swathes of territory, often for multiple publications that have common owners. The newsroom I worked for in Northern New Jersey in 2007 and 2008 had, at the time, maybe 15 reporters. It has three today, and they technically work for several publications covering the whole northern half of the state.

It’s grim. If democracy dies in darkness, as the saying goes, then it’s already on life support in areas across the country where the press is but a shell of its former self. But there are elected officials out there trying to do something about this problem, providing a glimmer of hope that better times are ahead.

Before we get to solutions, let’s drill down on the issue itself. One of, if not the, biggest difficulties local journalism faces is that its audience and revenue stream has been gobbled up by Big Tech, which not only has vastly superior ability to surveil and target ads to individual users, but steals content from news producers, whether through search and aggregator functions or thanks to users posting links to things they’ve read, against which the tech firms sell ads and collect even more user data.

Newspaper revenue dropped by more than 50 percent from 2002 to 2020, with the tech giants eating up most of that shift, as advertising dollars migrated. Journalists do the work, tech bros reap the rewards.

Today, by one estimate, Facebook alone controls 50 percent of the available display ad space online. Google and Facebook together receive 60 percent of digital ad revenue, with Amazon and a few others accounting for another 15 percent or so. So every news publisher in the country is, at best, fighting over 25 percent of the digital ad market. And while come big publications such as the New York Times have successfully turned to subscription models, the same just hasn't worked broadly for local news online.

Compounding that issue is the fact that Google has largely monopolized the digital advertising technology sector. Google both owns the underlying infrastructure that connects publishers and advertisers looking to sell and buy ad space, and it competes across that infrastructure as a publisher itself, selling ads on its properties such as YouTube. This allows it to manipulate prices, skim off the top, and give its own properties preferential treatment, all of which further harms local news outlets. Google estimates that it collects 35 cents of every dollar spent on digital ads.

So in order to start reversing local journalism’s decline, you need to 1) help publishers access the revenue that has shifted over to Big Tech in recent years, and 2) make the digital advertising market fair and transparent again.

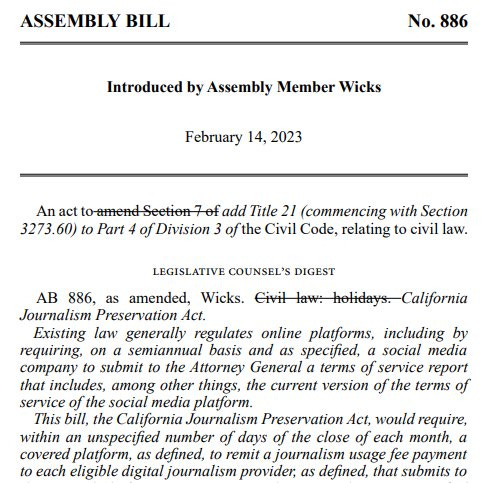

How to do that? On the first part, California Democratic Assemblymember Buffy Wicks recently introduced the California Journalism Preservation Act, which would require Big Tech firms to pay news producers when they sell ads against news content that was produced by journalists; publishers would be required to invest 70 percent of the money they receive from those payments back into their newsrooms, i.e., by hiring more reporters.

Wick’s bill is modeled off a federal bill, known as the Journalism Competition and Protection Act, which would allow news publishers to collectively bargain with Big Tech firms over compensation for their use of news content. That bill was recently reintroduced in Congress by Democratic Sen. Amy Klobuchar and Republican Sen. John Kennedy. In Australia, this idea was already passed into law and has been a gamechanger for local news outlets, driving up investment in newsrooms. Canada is also considering a similar move. Were California, and ultimately the U.S. as a whole, to join them, it would be a very big deal.

These efforts, at both the state and federal level, get at the first problem detailed above: Big Tech’s ability to profit off of the work done in newsrooms without providing fair compensation. And while Big Tech firms, most specifically Facebook, threaten to stop doing business in places that have such laws, when push came to shove in Australia, they caved and got in line.

But what about the second part, the monopolized ad markets? There’s been progress in that arena recently as well.

Last week, a bipartisan group of Senators in D.C led by Republican Mike Lee introduced a bill that would require the breakup of Google and Facebook’s digital ad businesses, as well as perhaps Amazon’s. Google is the main player though, and would be the most severely and directly impacted, since, as I said above, it owns both the technology to buy and sell ads, the middle “exchange” on which that business is conducted, and is a participant in the marketplace itself, giving it conflicts of interest every which way.

The bill would make it illegal for dominant firms to own and control different parts of the advertising technology businesses. For instance, a dominant corporation that runs advertising exchanges couldn’t also own the firms that buy and sell on those exchanges. To steal an analogy from Sen. Elizabeth Warren, no longer could corporations be the umpire and players in an individual market, which is what Google is doing now.

The introduction of Lee’s bill coincides with a lawsuit filed by the Department of Justice and several state attorneys general alleging that Google has used anticompetitive tactics and acquisitions to corner the digital ad market. “In pursuit of outsized profits, Google has caused great harm to online publishers and advertisers and American consumers,” the DoJ said. This week, Washington State Attorney General Bob Ferguson, one of the foremost proponents of challenging corporate power at the state level, joined that suit.

Were either Lee’s bill to pass or the DoJ to triumph and receive its requested breakup of Google’s ad tech business, it would go a long way toward making the digital advertising market work better for the participants, such as news publishers, rather than for a tech firm that managed to corner the infrastructure necessary to make it run.

As I wrote here, the decline in local news coverage is bad for communities for a whole host of reasons. In areas that lose newspapes, election turnout decreases, fewer candidates run for office, and incumbents win more often, while voters become more politically polarized, as their news consumption switches to hot-button, partisan federal issues that garner the most likes and rage retweets on tech platforms, as opposed to the nuts-and-bolts of local governance, such as bond issues and economic development deals.

Speaking of, lack of local news coverage also makes financing local projects more expensive, because investors demand higher rates from places with no media watchdogs. According to a 2018 study, municipalities that experience a newspaper closure pay an extra $650,000 on an average bond issue.

There are other steps than those outlined above, of course, that are required to truly rebuild the ability of local newsrooms to thrive in today’s world, including reining in the power of private equity firms to strip-mine newsrooms for parts, better regulating and limiting the ability of tech firms to surveil everything users do in the name of ever-more-finely-targeted advertising, and finally taxing the collection of user data. But the above measures at the state and federal level would be a great start.

Thanks for reading this edition of Boondoggle. If you liked it, please take a moment to click the little heart under the headline or below. And forward it to friends, family, or neighbors using the green buttons. Every click and share really helps.

If you don’t subscribe already and you’d like to sign up, just click below.

Thanks again!

— Pat Garofalo

The impact of losing local news on municipal bond rates is a creative argument. Nice to have framings that don't just preach to the choir but can persuade people with different priorities/values.

I am just getting up to speed on the ins and outs of freedom (and availability) of the press. The clarity and comprehensiveness of this post was really valuable. When I think about the implications of ChatGPT and other AI approaches - the internet scraping and regurgitation to generate ad revenue gets even more complicated - so many moving parts!