Five Years of Silence

How states and corporations use public records exemptions to cover up deal details.

This is Boondoggle, the newsletter about corporations ripping off our states and cities. If you’re not currently a subscriber, please click the green button below to sign up. Thanks!

The Tennessee legislature last week approved a massive new deal for a Ford electric vehicle and battery plant at a site about 50 miles east of Memphis. The legislation creates a “megasite” authority that will dole out $884 million in state funds: $500 million in corporate handouts to Ford and another $334 million in infrastructure and education spending. It’s the largest corporate subsidy deal in Tennessee history.

But the exorbitant cost isn’t the only issue. The legislation creates a public board to oversee the development of Ford’s project, and its powers include using eminent domain to seize land (in an unfortunate parallel to the failed Foxconn deal in Wisconsin, where eminent domain was used to acquire land that Foxconn subsequently didn’t use).

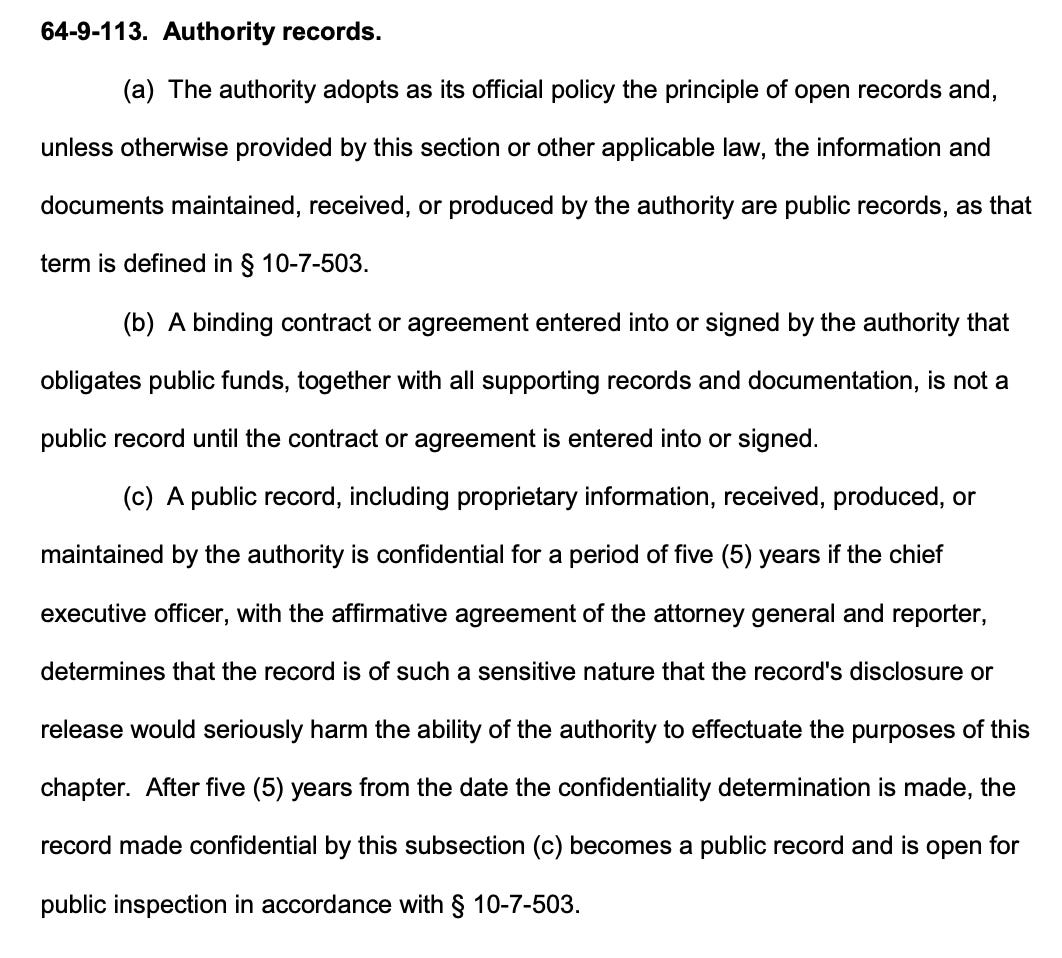

And the board is given wide latitude to keep documents and information pertaining to the deal out of the public eye, thanks to a huge exemption from state open records law. I’ve copied the relevant part of the legislation below.

There are two important parts of this statue worth noticing. The first is that nothing the board, Ford, or any other corporation involved in the project do is deemed a public record until the corporations agree to it, so the public will have little opportunity to weigh in as negotiations happen, putting them at an immediate disadvantage regarding anything that is eventually disclosed. This is the same tactic Amazon used to keep many of the HQ2 bids it solicited from being publicly disclosed, even to this day.

But it gets worse. The CEO of Tennessee’s new megasite entity can deem just about anything the board does secret for five years, putting it out of the reach of the state’s residents entirely. As Deborah Fisher, the executive director of the Tennessee Coalition for Open Government, put it, “That’s a whole lot of time to hide stuff you don’t want the public to know about.”

Though nearly every state has some sort of public records law, with most dating back to the 1960s or 1970s, many of them carve out wide exemptions for economic development deals. Even if those exemptions aren't explicitly in the law, economic development officials and agencies tend to use whatever latitude they can find in vague language or loopholes to keep economic development information under wraps. As Megan Rhyme, executive director of the Virginia Coalition for Open Government, told me, “Whatever is allowed to be withheld before or after [ a corporate subsidy deal] is routinely interpreted as broadly as possible.”

The stated theory for the creation of these exemptions is that subjecting deals to public records requests and ultimately disclosures will put the state at a competitive disadvantage when competing for corporate investment. In reality, the effect is exactly the opposite: Blind auctions drive up the prices states pay for corporate subsidies, because more information being out in the open means less opportunity for corporations to play states and cities off against each other.

That’s one of the reasons the interstate compact against corporate tax giveaways includes transparency measures that would apply across states. States and municipalities sharing information in real-time would make things better for taxpayers, not worse.

Of course, there’s a more cynical explanation for why lawmakers and economic development officials love public records exemptions: It lets them cover up shady dealings while bragging about the supposed upside of the deals they craft.

Case in point, journalists in St. Louis use a public records request last year to discover that Energizer received $3 million in tax credits, including some funding from a program meant to prevent companies from relocating to other states, without actually threatening to leave. That information wouldn’t have come out without adequate public records access. Local officials would have instead been able to tout the supposed benefits of the deal, with taxpayers none the wiser.

I do think, though, that local journalists get pretty annoyed at and offended by public records restrictions like these, in a way they don’t about corporate subsidy deals in general. We’ll see if that results in any sustained pressure on Tennessee lawmakers to explain why they believe this level of secrecy is necessary for a project they all say will be an economic bonanza for the state.

Meanwhile, this paper I released a few months ago has some recommendations for policies that would ensure corporate subsidy deals aren’t hidden from the public. Share it with your local lawmakers, if you’re so inclined.

ONE MORE THING: This is a good paper from Good Jobs First about how to improve what’s known as GASB 77, which is the funny-sounding name for a very important accounting standard that, in theory, should force state and local governments to disclose how much money they lose to corporate subsidy deals. In practice, it’s got some holes, so the Good Jobs First folks have eight recommendations for patching them up. You can read the paper here.

Thanks for reading this edition of Boondoggle. If you liked it, please take a moment to click the little heart under the headline or below. And forward it to friends, family, or neighbors using the green buttons. Every click and share really helps.

If you don’t subscribe already and you’d like to sign up, just click below.

Finally, if you’d like to pick up a copy of my book, The Billionaire Boondoggle: How Our Politicians Let Corporations and Bigwigs Steal Our Money and Jobs, go here.

Thanks again!

— Pat Garofalo