This is Boondoggle, the newsletter about how corporations rip off our states, cities, and communities, and what we can do about it. If you’re not currently a subscriber, please click the green button below to sign up. Thanks!

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis recently proposed that his state institute a sales tax holiday on guns and ammunition. If approved, the state’s sales tax will not be applied to purchases of those items for a set period of time this summer. The Georgia State Senate, a couple of weeks later, advanced a bill to do the same over a period that coincides with hunting season.

I am personally horrified at the idea of making killing weapons even cheaper, but no one is here for my gun control takes. And these proposals also illustrate something important in the realm of economic policy: The enduring appeal of the state sales tax holiday — despite the fact that the available evidence shows sales tax holidays are a scam, don’t provide the promised benefits, and result in fewer public resources and higher taxes for all of us.

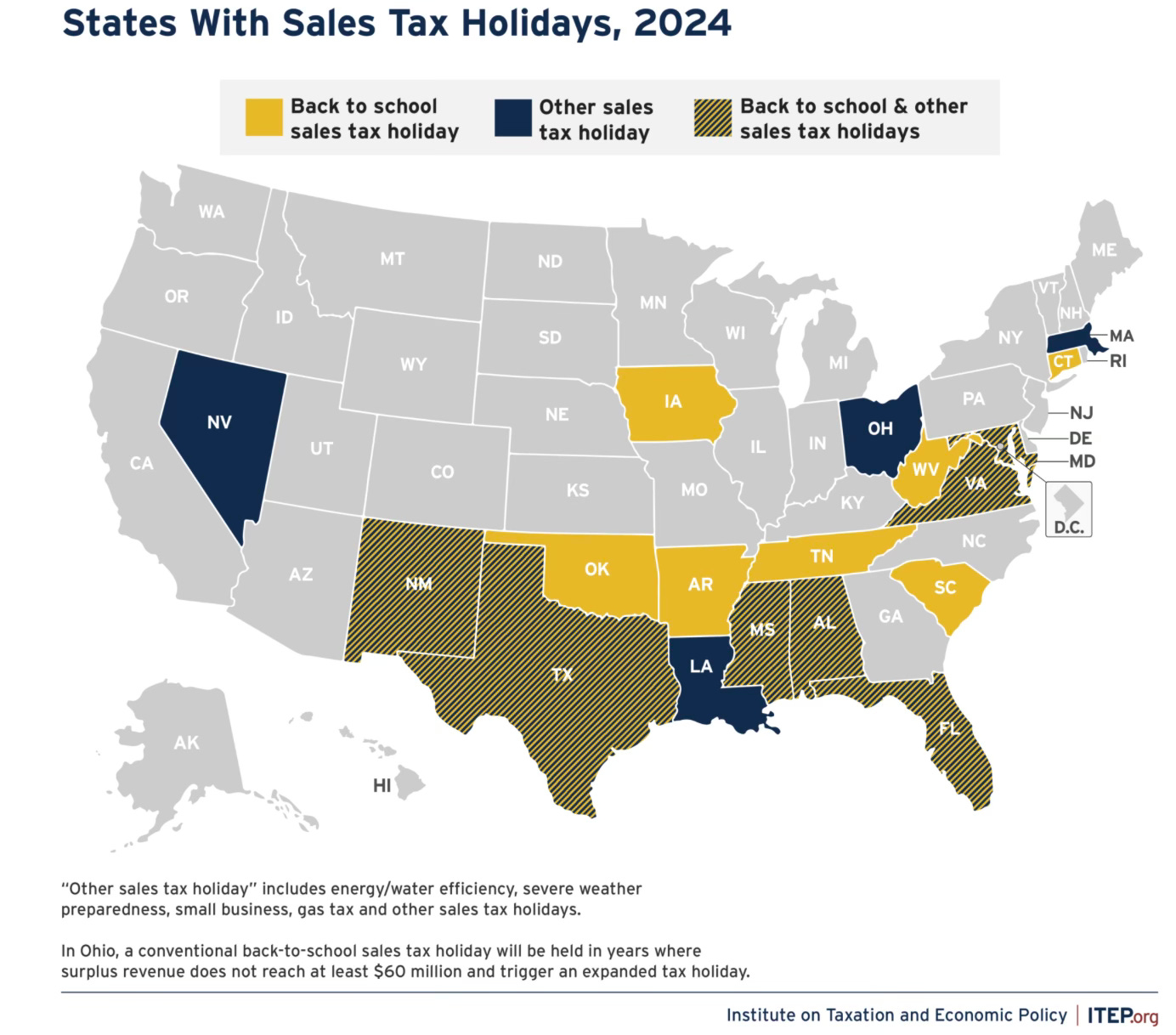

Again, a sales tax holiday is a period of time during which the state sales tax is waived either on all consumer products or on a select set of purchases. Some of the most popular holidays coincide with back-to-school season and disaster prep, i.e., buying things to prepare for hurricane season. According to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 19 states held some sort of sales tax holiday last year:

The first of the modern slew of sales tax holidays took place in New York in January 1997, and was adopted in response to New Jersey eliminating the sales tax on clothing purchases. New York lawmakers were trying to boost their own domestic retailers, as opposed to having New Yorkers cross over into New Jersey to buy clothes.

But thus were the proverbial floodgates opened. Florida, which currently leads the nation in the number of sales tax holidays, implemented its first in 1998, and then Texas went along the year after that. The number of states participating has ebbed and flowed ever since — with states tending to repeal their sales tax holidays when their finances take a hit during economic downturns — but the 19 states that participated in 2024 is tied with 2010 for the most in a single year.

The stated aim of these holidays is generally the same, year in and year out and regardless of the politics of the state in question: Providing a break to “hardworking” families by lowering the cost of some subset of goods that have been deemed necessities, or as a general sort of tax cut.

Especially since most states have tax systems that take more from the poor than the rich, with sales taxes largely to blame, sales tax holidays are often even more explicitly pitched as benefitting the lowest earners in a state.

However, those benefits don’t actually materialize, for a very simple reason: People with less money aren’t generally able to shift a bunch of purchases in order to coincide with a sales tax holiday, as they’re on an extremely fixed budget. In fact, according to a 2010 study by the Chicago Federal Reserve, households with incomes under $30,000 and single-parent households derive essentially no benefit whatsoever from sales tax holidays. Instead, “the wealthiest households and households consisting of married parents and young children have the largest, statistically significant response.”

Other research has confirmed that the end result of sales tax holidays is simply a shifting of purchases, rather than a boost that wouldn’t have occurred in the absence of the holiday. And that makes sense: We all only need so much household stuff, so getting it slightly cheaper one month simply means we don’t purchase it at all in another month, or that we make the same purchases, roughly, month to month and year to year, sometimes getting a tax break and sometimes not, but without fundamentally changing our shopping patterns.

So the chief effect of a sales tax holiday is not actually on the shopper’s behavior, which is the stated public policy goal. There are three other real effects to point to, though, none of them good.

First, the proliferation of these holidays has put a significant dent in state and local budgets, since the sales tax provides about 14 percent of the average’s state’s revenue and 5 percent of the average municipality’s. In 2024, sales tax holidays cost states and localities more than $1.3 billion in revenue, which is actually less than the $1.6 billion loss that occurred in 2023. Again, this is why states tend to repeal them when their finances are headed in the wrong direction.

Also, to make up for that loss, governments wind up setting the usual sales tax rate higher than it would otherwise have been, which means that residents of a state may actually be paying higher taxes the rest of the year to make up for the break they supposedly receive due to sales tax holidays.

Second, there’s some evidence that retailers game sales tax holidays, marking up their products in the days before and then pocketing the difference when the sales tax is removed. I’ve tried to find more research or data regarding which types of corporations and businesses benefit most from sales tax holidays — because my suspicion is its bigger box stores and national chains, not local retailers — but to no avail. (Please, any economic researchers out there, look into this!)

Third, and probably most importantly, politicians almost certainly derive significant political benefits from implementing sales tax holidays and trumpeting their existence. Much like corporate subsidies help build political capital for incumbent lawmakers by allowing them to claim credit for creating jobs, sales tax holidays allow them to claim credit for tax cuts, even if the actual benefits to the average person are illusory at best, or even negative.

Indeed, you better believe DeSantis is going to make noise about his “Second Amendment summer” tax holiday, even when it ends up dinging the state budget.

Political actors are aided in this by local media coverage that tends to, at best, simply report the existence of sales tax holidays, and at worst act as a press release, actively cheerleading them and their proponents. (Here’s an example of a better piece that at least attempts to grapple with the tradeoffs.)

But rest assured that whatever accolades political actors receive, sales tax holidays are ultimately more about moving votes than moving dollars in a meaningful way, and they probably cost you more than you save in the long run.

SHAMELESS SELF-PROMOTION: My neighbor Nick Sementelli and I have a long piece in Greater Greater Washington breaking down why D.C. should not subsidize a new stadium for the NFL’s Washington Commanders and explaining why most “economic impact” studies about stadiums are nonsense. Read it here.

SIMPLY STATED: Here are links to a few stories that caught my eye this week.

States are banning the Chinese AI app DeepSeek from government devices and networks.

Texas will allow employees at a SpaceX launch site to determine whether they want the site to become its own municipality.

Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker wants to crack down on crypto ATMs.

Indiana legislators advanced a bill that would enable the state to try to entice the Chicago Bears to leave Illinois.

Nevada legislators are aiming to knock often phony and fraudulent “ghost kitchens” off of delivery apps.

Several measures to rein in Virginia’s data center industry have been blocked or watered down.

Thanks for reading this edition of Boondoggle. If you liked it, please take a moment to click the little heart under the headline or below. And forward it to friends, family, or neighbors using the green buttons. Every click and share really helps.

If you don’t subscribe already and you’d like to sign up, just click below.

Thanks again!

— Pat Garofalo

The only thing dumber than sales taxes are sales tax holidays, particularly when they encourage purchases of items that are contrary to the public good.